Ladakh (August 2014)

The English translation of a section of the book Gesù in India? (Jesus in India?) where it is reported my visit to Ladakh and to Hemis’s Monastery where, at the end of nineteenth century, have been found crucial manuscripts about possible stay of Jesus in India.

Translation of full book is in process and it will be soon available in English as well.

The synopsis is already available, you can read it clicking here.

A big thanksgiving is due to PJ Moar who efficiently helped with editing.

Manuel Olivares

It was a journey I had been planning for several years.

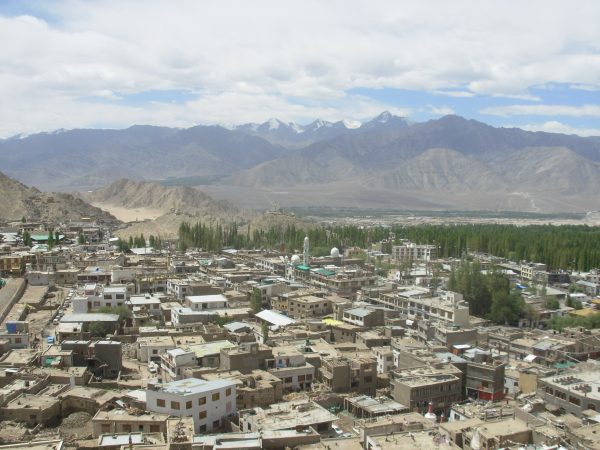

I decided to visit Leh, the capital of Ladakh, an autonomous “state within a state” (Ladakh is officially part of Jammu and Kashmir state).

After arriving from Delhi I immediately begin experiencing Acute Mountain Disease (AMD). I settle in one room of a simple guest house in Changspa, the most touristic area of town, offering plenty of expensive, upmarket places suitable only for the cul serré.

The guest house is ideal to stay for a few days while acclimatising to the altitude and its effects (the AMD).

In the following days, I visit the old town, a much more interesting place. Indeed, I soon move there. It has the advantage of being closer to the bus station, which I would like to use for visiting several places.

In the following days, I visit the old town, a much more interesting place. Indeed, I soon move there. It has the advantage of being closer to the bus station, which I would like to use for visiting several places.

The new guest house is for experienced travelers. It has a wide courtyard and, in one corner, a long table. This, like everything else here, including the unstable chairs, is in a poor state, although it is perfect for socialising in the evening. Here the guests spend time together, drinking beer or local liquors, smoking, chatting and sharing mostly travel stories. It is like being back in the 1970s, with cheap travels in Asia and nomadic, adventurous lifestyles. It is the ideal place to travel from, leaving heavy baggage behind.

And then, the adhān from nearby Mosque makes impossible, for a Westerner, to forget he is “somewhere else”.

I leave more than one time, just with basic things, leaving my baggage, money and laptop safe in my room, in Leh, without knowing exactly when I would return, choosing whether or not to sleep out of town according to the flow of events.

Ladakh is archaic and remote. It is sometimes difficult to use the internet, telephone cards are useless and it seems that no one has the patience to follow the necessary procedures to get local ones.

It is easy to meet interesting people, especially on government bus; travelers of other times (maybe because the place is a pre-modern one). With them I’ve sometimes scheduled vague appointments — without disposing of current, efficient communicative facilities — that were missed, leaving space and time for new encounters and new tales.

Everything happens in the harsh yet welcoming frame of an almost desert, high mountain environment. The cultural context is Tibetan with a strong Muslim minority (mostly Kashmiri).

The monasteries overlook small, humble villages. The Indus river and its tributaries flow, meagre on their riverbeds. The vegetation mottles a vaguely lunar landscape of irregular altitudes and pinnacles.

The air is mercilessly dry, and scant oxygen means that movements and frequent climbs are strenuous.

The first visit is to Thiksey (in fact it is unscheduled. I had planned to go elsewhere, but underestimated the chaos of the bus station). Here, it is possible to visit one of the finest Ladakhi monasteries, which rises with the village up the side of mountain.

The stone block monastery-village is sometimes, mazy, with short underpasses and tunnels. In one of these I find a board of a monastic school, whose entrance overlooks the ravine. It is easy to imagine a system of wooden stairs giving access to the upper floor, above the gallery itself, where segments of ancestral knowledge have been transmitted, for several centuries, to young monks.

The stone block monastery-village is sometimes, mazy, with short underpasses and tunnels. In one of these I find a board of a monastic school, whose entrance overlooks the ravine. It is easy to imagine a system of wooden stairs giving access to the upper floor, above the gallery itself, where segments of ancestral knowledge have been transmitted, for several centuries, to young monks.

I lose my way, suffering from shortage of oxygen. My mind is overwhelmed by the charm of the place and I have no hurry to get — or to know how to get — anywhere. To be there, in the gallery, next to the monastery school, is sufficient. I don’t hesitate to take a break and get my breath back.

A monk comes out from the school. He is a child, probably no more than eleven or twelve years old.

«Where are you going?», he asks me with unexpected authority.

«To the monastery», I answer, almost comically overawed by him.

I, a big man, cowed by a child, but you should have seen the glance, the dignity. He was clearly a wise adult in a child’s body.

I follow his directions, soon reaching the monastery, which is famous for a beautiful statue of the Maitreya Buddha.

I follow his directions, soon reaching the monastery, which is famous for a beautiful statue of the Maitreya Buddha.

Thiksey’s monastery belongs to Gelugpa (or Geluk) school, that of the current Dalai Lama. It has an intimate library housing many manuscripts on rice paper, each meticulously protected between two small wooden boards and in cloths embroidered with mythical and doctrinal motifs.

The monastery’s terrace overlooks the green stained valley where the Indus river, a trickle of water, flows. The wooden interiors are snug and hieratic. The monks are particularly affable.

I return to Leh in the evening, not wanting to stay anywhere else. On my return, I stop in Shey at a nunnery (a monastery for nuns) called Naropa Pothang.

It belongs to the Drukpa school, the same of Hemis’s monastery.

During my time in Leh, I bought the book Ladakh: A Land of Magical Monasteries, which mentions the manuscripts of Hemis, connecting it to the nunnery in Shey. It explains that to access the manuscripts it is necessary to obtain a special permit from the Head Lama. It is not clear whether he is the abbot of the monastery or the Gyalwang Drukpa.

I speak to someone in the nunnery reception, telling her that I would be going to Hemis and would like an appointment with the Head Lama (my online researches revealed that “fortunately” the monastery has no website or email address). She tells me that the Head Lama is in Nepal (on the Druk Amithaba Mountain — then we’re talking about Gyalwang Drukpa even if will emerge, later, the crucial role of Hemis’ abbot —) and I can talk with his attendant of whom she gives me the name and the mobile number.

Hemis

Hemis

The next day, I leave for Hemis. Again, at the bus station I face problems. The place is quite remote. Indeed, the book Ladakh: A Land of Magical Monasteries advises visitors to go to the nearest town, Karu.

However, there are no buses to Karu either, so I decide to hitchhike. It’s an effective option in Ladakh. I did this on the previous day when returning from Shey, tired of waiting for the bus or minivan.

It’s not difficult to get a lift, because it’s an opportunity for drivers to earn a little money. One guy stops with his nice Toyota jeep. He asks me quite a lot, but I have a good feeling. I accept his deal and he will take me directly to Hemis.

The monastery occupies a niche in the mountains. Secluded and almost impregnable, it has been used for centuries to preserve ancient and precious goods.

Firstly, I ignore the monastery choosing to visit the nearby Gotsangpa’s hermitage. Gotsangpa was one of the first saints of Drukpa tradition. He lived between 1189 and 1258, being the founder of To Druk: “High Drukpa”.

“Got” means “vulture”, tsang means “nest”. In Tibet and Ladakh vultures have their nests in the highest mountain areas.

In one of these vulture’s nests, a cave in Ladakh not far from the future monastery of Hemis, Gotsangpa spent years in meditation with the pledge: «You, the bird, the rock and I: the man. Until I realise the oneness of the three, I will not leave this spot»[1].

On Gotsangpa’s cave, centuries later, a hermitage was built in his name. At more than four thousand metres above sea level, above this place are only the barren and rocky peaks of the mountains. Some visible peaks are snow-capped, but what is most fascinating is the quality of silence.

On Gotsangpa’s cave, centuries later, a hermitage was built in his name. At more than four thousand metres above sea level, above this place are only the barren and rocky peaks of the mountains. Some visible peaks are snow-capped, but what is most fascinating is the quality of silence.

Some verses come to mind of Śāntideva, as meticulously reported by Ananda Coomaraswamy:

«Fain would I dwell in some deserted sanctuary, beneath a tree or in caves, that I might walk without heed, looking never behind! Fain would I abide in nature’s own spacious and lordless lands, a homeless wanderer, free of will, my sole wealth a clay bowl, my cloak profitless to robbers, fearless and careless of my body»[2].

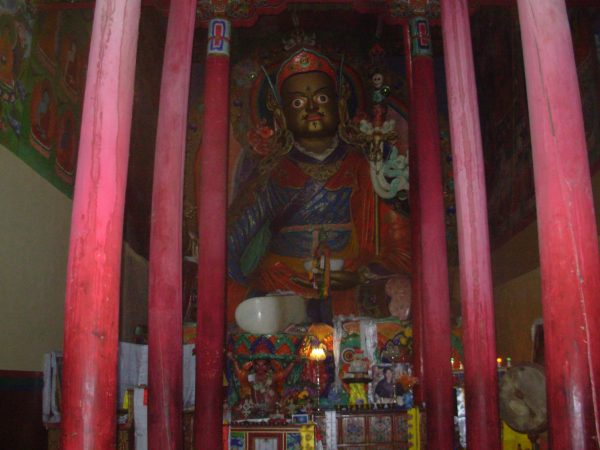

Arriving at the hermitage, I reach Gotsangpa’s cave. It is difficult to describe how rarefaction and the silence of the place saturates everything: the opening of a door, the creaking of the wooden planks under foot, the smile of the young monk who spontaneously leads me.

In the back of the cave there are some statues of Buddha and Padmasambhava[3] (in the photo), in a shrine.

In the back of the cave there are some statues of Buddha and Padmasambhava[3] (in the photo), in a shrine.

A guy is meditating sitting on the floor. The monk makes me touch the low ceiling of the cave. It exudes moisture. In winter time, at minus thirty degrees, the place is probably freezing.

I sit beside the guy who meditates with open and welcoming palms resting on his knees. A monk sits in front of us, behind ritual bells, a large circular drum – in vertical position on wooden support – and a small table with a Tibetan manuscript.

After a few minutes a puja (celebration) begins. The monk beats the drum repeatedly with a wooden rod. He reads the contents of the manuscript following the rhythm of the drum. Sometimes he takes a break, playing a typical Tibetan trumpet, then again he beats the drum rapidly while reading the manuscript.

Again Śāntideva:

«Fain would I go to my home the graveyard, and compare with other skeletons my own frail body, for this my body will become so foul that the very jackals will not approach it because of its stench. The bony members born with this corporeal frame will fall as under from it, much more so my friends. Alone man is born, alone he dies; no other has a share in his sorrows. What avail friends, but to bar his way? As a way farer takes a brief lodging, so he that is travelling through the way of existence finds in each birth but a passing rest. . . ..»[4].

Again a sound of Tibetan trumpet, again some passages to be read, the drum to be beaten, and then the cave becomes totally silent.

I open my eyes, discovering a small mouse moving among holy paraphernalia.

I leave the cave for the hermitage’s terrace.

The guy who was meditating beside me is also there. He looks at me, friendly and smiling.

«I saw you coming up», he starts.

«I saw you as well», I answer, «ahead of me, on the mountain’s stairs, to climb has been exhausting!».

«Even for me», he says, «you’ve been stimulating, I didn’t want you could join me because I was too tired».

«You also; I didn’t want you — once in the hermitage — could think: that lazy guy has not been able to climb!».

We laugh. His name is Miro, a Slovak, doing a long journey in India and Nepal to think about his future. He has left his job. He’s not engaged and doesn’t know if he wants a “normal” kind of life.

We reach another part of the hermitage where another puja is in progress. Every sound is amplified by a slight rumble in the lunar silence of the place. They offer us, several times, some butter tea.

I would like to remain for the night, to lose the sense of time, of plans. I would like to stay here and absorb everything, without the need to return anywhere, being able to lose the whole idea of return.

I will ask a monk if it is possible to stay here for the night without any prior reservation.

Miro, when the puja is finished, encourages me: «I already came here, yesterday. A young monk asked if I wanted to stay for the night», but he’s more concerned about food.

The monks are not so welcoming. Most of them are old, probably living in the hermitage for a long time and never leaving. How could they? The climb to get here has worn down one young guy, Miro who is 32, and one almost as young…me. There is no other way to get here. We decide to ask for some food.

«Lunch is ready!», a monk tells us.

We follow him on other stairways, on the ridge of the mountain, again climbing, with our faces shredded by arid wind. We arrive at one small, stony building: the hermitage canteen. Outside, on a small wall, are three cauldrons.

Many monks have arrived before us, but none fills his dish till we hear the sound of a bell.

Miro and I, according to my knowledge of monastic rules, must wait our turn until the last monk has taken his food. Then, the monk who has been leading us indicates a small tank of water, ordering us to wash our hands. We obey. I would like to see inside the canteen, but I simply ask: «Do we eat here?», indicating the inside.

«No!», answers the monk, «wait!». Meanwhile, the cauldrons disappeared.

The wind from snow-capped peaks, starts to become frosty.

The monk entered the canteen and has now returned with two dishes of rice and boiled vegetables. He gives us the dishes and returns inside the canteen.

Miro and I look at each other slightly confused. He didn’t even give us a fork!

«Let’s sit there», I propose, indicating a low wall.

We eat the rice and tasteless vegetables with our hands. It is almost an effort to speak as we absorb such a wonderfully harsh environment. We speak a few words about Italy, a few about Slovakia and a few about our lives, Ladakh, and the reasons for being on that mountain, almost unwanted by surly monk-hermits.

After our meagre meal we wash our dishes. The monk who led us to the canteen is passing nearby. I don’t think there is any chance to be welcomed for the night, but I ask him anyway.

The answer is very direct: «No!».

I say to Miro: «I will not go back to Leh, today, but will rent a room in the monastery’s guest house».

«I’m staying with a family in the village. I pitched my tent in their land», says Miro.

«Wow!», I answer, «the home-stay would be the best option!».

We start walking in the direction of the Hemis monastery and village, leaving the hermitage behind us.

Unlike Thiksey, Hemis’s village is not combined in the same block as the monastery; it has developed independently in a niche of the valley below.

It is rather secluded, composed of around twenty stone houses beside a small stream. Just houses, no shops, but a fountain with an iron lever and a few dogs wandering around.

We go to the house where Miro is hosted, slightly outside the village. The owners are not there.

We head towards the stream, talking with some locals. People look at us in a neutral manner, with neither curiosity nor hostility.

«I’m looking for a room», I publicly say, «has someone a room to rent for this night?».

Fortunately, Ladakhi have a good knowledge of English.

A girl brings me to her house, twenty metres from the stream, but isolated from the others. She shows me a decent room, but I’m not happy with the price. It is too high and, despite understanding the need for locals to earn money from foreigners, I prefer to be hosted by more simple people. I thank her and go back to the stream.

Miro looks at me quizzically.

«Don’t worry», I make him understand.

I cross the stream and begin walking through the alleys of the village. A man is walking in the opposite direction, in an alley so narrow that we can barely pass each other.

I greet him and ask directly:

«I need a room, could you please help me?».

He has two vaguely blue eyes on a face dried by the Himalayan wind and furrowed by wrinkles. His reactions are slow and placid, in keeping with the vibe of the place.

«I can show you the room we use for our relatives, if for you it is okay…».

«Great», I answer, «let’s see it!».

The room is very nice, better than the former I saw. It is a kind of studio with a kitchen. Several mattresses and pillows at the sides of the room mark its perimeter.

On each mattress there are, neatly folded, sheets and blankets. Beside each mattress there is a small, carved table with images of dragons (drukpa).

«How much money I can give you to sleep one night here?» I ask.

He’s a little confused and doesn’t answer; he is the person I was looking for; a pure local who has never thought to profit from a visiting foreigner.

I insist: «How may I reciprocate your politeness? I’d like to pay for the disturbance».

«Give me what you want», he answers.

We agree to a reasonable amount and I tell him about Miro. He’s also welcome and we can also have dinner.

I join Miro and he’s amazed by my enthusiasm. He wants to see the room.

The room, which is pretty, simple, functional and clean, pleases him.

The house, in general, is really disarming, with a small vegetable garden, some clothes hanging to dry and a bundled-up baby in the arms of a toothless grandmother. And then there is our host: blue-eyed, calm and vital, attentive and kindly, yet suggesting a hard life.

«I will dismantle the tent and join you», says Miro.

«Alright», I answer, «I propose that we pay extra to have dinner with them».

«Sure», answers Miro.

Soon we’re all in the kitchen of the house, sitting on mattresses marking the perimeter of the room.

Soon we’re all in the kitchen of the house, sitting on mattresses marking the perimeter of the room.

Our hosts switch the television on and then soon switch it off.

The wife of our host is quietly busy cooking. Soon, the food is ready and served in abundance.

There are no real conversations, except for short moments, but the company is pleasant, the light very soft and we enjoy this kind of intimacy.

The following day, sitting on the low wall of the house, looking at the simple vegetable garden and drinking our tea, Miro offers some deep reflections: «I think I’d like to live as they’re doing», he says.

Indeed, in that simplicity there is nothing, except the essentials!

I am also inclined to these kinds of reflections and every day I am more attracted by a “way out from the world”.

After a few days, in fact, I am there again, but this time alone.

Miro bought a 1988 Enfield motorbike in Manali[5], thinking to re-sell it upon leaving India.

That morning we sipped tea looking at the vegetable garden used for the subsistence of our welcoming Ladakhi family. Then we returned to Leh on his Enfield, with our faces dried up by the wind, enjoying landscapes of irregular peaks and humble villages.

We vaguely planned to travel together, in the evening, to a meeting. However, the difficulties of language and communication discouraged us, so we opted for a final farewell.

To salute Miro has been to salute a universal companion of research. Again, words by Coomaraswamy’s book can help to express what is probably the illusory nature of each separation:

«Thou goest thine, and I go mine —

Many ways we wend

Many days and, many ways,

Ending in one end.

Many a wrong, and its curing song

Many a word, and many an inn:

Room to roam, but only one home

For all the world to win».[6]

Again to Hemis

The return to Leh, after the experience in the hermitage and the night in the village, has been quite frustrating.

After an evening of chat, drinking poor Indian whiskey, smoking my pipe and listening the stories of my neighbour, Derek, about Eelam[7] ― whose palms were largely beheaded by a never ending and merciless war and where everything expressed a clear feeling of death ― I cannot avoid to plan a new visit to the Ladakhi family.

And then, if it is true that the journey is more important than the destination, it is even important to avoid excessive distractions, missing the chance to reach it.

My first visit to Hemis brought results. I visited the famous monastery’s museum, talking with the person in charge, Jigme, and, as already noted, the personal secretary of the Head Lama.

I asked about the manuscripts and the possibility of getting a meeting with the only person who can authorise their viewing.

Jigme confirms what I read in the booklet The Monasteries of Hemis, Chedme and Dagthag, on sale in museum’s shop: the manuscripts are held in a secret room called, by locals, dzodnag.

Only the Abbot of Hemis, His Holiness Taktsang Rinpoche, can break the room’s seals, enabling the access to the manuscripts.

However, Taktsang Rinpoche lives in Lhasa, and in the same booklet it is written that he has no objection to access being granted to sincere researchers. Indeed, he has officially requested that they to be helped in the search of old documents.

However, somebody joined the monastery with a letter written by the Abbot but, still, he could not see the manuscripts.

The booklet reports that the only entrance to dzodnag is by the private room of Abbot.

After Iearning all of this, I consult Jigme, hoping for more information. As with other monks I have talked with, Jigme says that nobody knows where the manuscripts are and that even the location of dzodnag is a mystery.

I reach the house of the Ladakhi family who previously hosted me and Miro. I will spend a couple of nights there.

On this second visit I become more aware of the quiet nature of the people and their equally quiet environment, reminiscent of the Arctic.

The lower slopes feature a scattering of trees and along the mountain ridges there is limited vegetation with a scattering of bushes. This gives way to bare ground with a moss or lichen-like cover.

The animals are silent, too, although from time to time this is broken by the croaking of a bird.

The same silence pervades the Spartans and simple interiors.

I am able to begin some bare conversation, facilitated by my hosts’ minimal knowledge of English and my basics of Hindi.

Their mother tongue, however, is Ladakhi, similar to Tibetan. But our limited conversations are not caused by language differences. It is merely their way to use few and simple words.

I am always the only one trying to lead the conversation, but they answer in a gentle, even sweet manner, then again become silent.

Therefore, during my stay, we share a silence without any embarrassment, in tune with silent environment.

The words, useless, roll down the ridges of consciousness, as stones sink in a river. Then it is possible to feel the fullness of the golden silence, oldest of the oldest expressions of creation.

I clearly feel whatever it is said is awkward and I try to be a simple witness of these moments. And, after the words, the thoughts start falling too, along the creaking of an old-wooden door and, finally, the specious Descartes’ assumption: «I think therefore I am» reverses, giving way to a more reliable: «I am therefore I am».

This could really neutralize the arrogance of the West that’s paving the way to its prophesied decline[8].

During my short stay in the village of Hemis, I get to know the grandson of the householder. He is around sixteen and became a monk when he was nine. He’s now studying in a monastic school.

I tell him the main purpose of my visit. He also doesn’t know anything about the dzodnag and tells me the Abbot of Hemis’ monastery is in Tibet. He gives me a card with the image of Taktsang Rinpoche beside the Gyalwang Drukpa who lives in Nepal.

I think I will be forced to visit that country to get a new visa for India. Before the challenge of visiting Tibet (mostly its monasteries and monks) I can focus on a more simple stay at the head-lineage’s monastery, trying to progress with the search.

***

My stay, in October 2014, on Druk Amitabha Mountain will be very intense.

It will be preceded by an email that will get a quick but hazy answer.

I will remain around ten days in a Nepali nunnery, soliciting an interview with the Gyalwang Drukpa.

I will have just a couple of meetings with a nun of his staff who will give me no guarantee of a meeting with His Holiness.

«He’s constantly busy», she will tell me more than once. «I will do my best but it will be difficult, for you, to meet him».

She will take notes about the book I’m writing asking why I decided to do it.

During the second meeting she will ask me explicitly: «Do you want to write this book to become famous or for other reasons?».

«I appreciate this question», I reply, «I think it is important to reduce the gap between East and West, if we are able to demonstrate we have a crucial figure as Jesus in common we could make important steps forward…and, then, Christianity really needs a deep regeneration, to better contribute to the formation of a new, universal man!».

She is also satisfied with my answer, but it is approaching the time of an important pilgrimage, led by His Holiness, in India, in historical places of the first Buddhism: the Pad Yatra.

Then, Gyalwang Drukpa will leave the quiet of the Nepali mountain a few days before me, followed by the majority of the nuns.

With a new visa on my passport, I will return to Varanasi (where I live most of my time while I’m in India) with some more references about Drukpa school and, in particular, one of its offices specifically dedicated to publications, in India.

***

Before leaving Hemis I cautiously ask to young monk if he’s happy (as I feel) with his condition and if he has sometimes an even slight desire of mundane life.

He answers in a lapidary way: «We (monks) are different!».

He then reverts to his natural condition of silence.

We remain silent for few minutes then he gets up and, taking his leave in an essential but affable way, he leaves me alone in the guest room, watching the vanishing of my thoughts in the golden silence of that — unforgettable — place.

<iframe style=”width:120px;height:240px;” marginwidth=”0″ marginheight=”0″ scrolling=”no” frameborder=”0″ src=”https://rcm-eu.amazon-adsystem.com/e/cm?ref=tf_til&t=viverealtrime-21&m=amazon&o=29&p=8&l=as1&IS1=1&asins=B07YCVCZQ9&linkId=a155e960d2b53c0edc21fff2922f3678&bc1=FFFFFF&lt1=_top&fc1=333333&lc1=0066C0&bg1=FFFFFF&f=ifr”>

</iframe>

[1] Tsering N., The monasteries of Hemis, Chemde and Dagthag, New Delhi, p. 7.

[2] Ananda K. Coomaraswamy, Buddha and the Gospel of Buddhism, op. cit., p. 322.

[3] «Padma Sambhava was an 8th century Indian Buddhist sage and Tantric magician, who was invited to Tibet by Santarakshita, an Indian Buddhist master. With his great spiritual power, he created the conditions for the propagation of the teachings of Vajrayana Buddhism in this world.

[…]

In Sanskrit Padma means lotus flore and Sambhava means born from. In Tibet and Ladakh, Padma Sambhava is also known as Guru Rimpoche».

In: Gibbons Bob-Sian Pritchard Jones, Ladakh land of magical monasteries, Pilgrims Publishing, Varanasi, 2006, p. 25.

[4] Ananda K. Coomaraswamy, Buddha and the Gospel of Buddhism, op. cit., p. 322.

[5] A famous mountain place in Indian state of Himachal Pradesh.

[6] Ananda Coomaraswamy, Buddha and the Gospel of Buddhism, op. cit., p. 194.

[7] Area in North of Sri Lanka mostly populated by Tamil who unsuccessfully attempted, through a long civil war, to get independence.

[8] Here there is a reference to a book, published in 1918, with a probable prophetic title: The decline of the West, by Oswald Spengler.

English

English Italian

Italian